How do we make machines understand text data? We know that machines are supremely adept at dealing and working with numerical data, but they become sputtering instruments if we feed them raw text data. The idea is to create a representation of words that capture their meanings, semantic relationships, and the different contexts in which they are used. That’s what word embeddings are – the numerical representation of a text.

And pretrained word embeddings are a key cog in today’s Natural Language Processing (NLP) space.

But the question remains – do pretrained word embeddings give an extra edge to our NLP model? That’s an important point you should know the answer to. So, in this article, I will shed some light on the importance of pretrained word embeddings. We’ll also compare the performance of pretrained word embeddings and learning embeddings from scratch for a sentiment analysis problem.

Learning Objective

- Understand the importance of pretrained word embeddings

- Learn about the two popular types of pretrained word embeddings – Word2Vec and GloVe

- Compare the performance of pretrained word embeddings and learning embeddings from scratch

Table of contents

- What are Pretrained Word Embeddings?

- Why Do We Need Pretrained Word Embeddings?

- What are the Different Pretrained Word Embeddings?

- Google’s Word2vec Pretrained Word Embedding

- Stanford’s GloVe Pretrained Word Embedding

- Case Study: Learning Embeddings from Scratch vs. Pretrained Word Embeddings

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Check out Analytics Vidhya’s comprehensive and popular Natural Language Processing (NLP) using Python course!

What are Pretrained Word Embeddings?

Let’s answer the big question: what exactly are pretrained word embeddings?

Pretrained Word Embeddings are the embeddings learned in one task that are used for solving another similar task.

These embeddings are trained on large datasets, saved, and then used for solving other tasks. That’s why pretrained word embeddings are a form of Transfer Learning.

Transfer learning, as the name suggests, is about transferring the learnings of one task to another. Learnings could be either weights or embeddings. In our case here, learnings are the embeddings. Hence, this concept is known as pretrained word embeddings. The concept is known as a pretrained model in the case of weights.

You can learn more about Transfer Learning in the below in-depth article:

But why do we need pretrained word embeddings in the first place? Why can’t we learn our embeddings from scratch? I will answer these questions in the next section.

Why Do We Need Pretrained Word Embeddings?

Pretrained word embeddings capture a word’s semantic and syntactic meaning as they are trained on large datasets. They can boost the performance of a Natural Language Processing (NLP) model. These word embeddings come in handy during hackathons and, of course, in real-world problems.

But why should we not learn our embeddings? Well, learning word embeddings from scratch is a challenging problem due to two primary reasons:

- Sparsity of training data

- Large number of trainable parameters

Sparsity of Training Data

One primary reason for not doing this is the Sparsity of Training Data. Most real-world problems contain a large volume of rare words, and the embeddings learned from these datasets cannot arrive at the right representation of the word.

To achieve this, the dataset must contain a rich vocabulary. Frequently occurring words build just such a vocabulary.

Large Number of Trainable Parameters

Secondly, the number of Trainable Parameters increases while learning embeddings from scratch. This results in a slower training process. Learning embeddings from scratch might also leave you unclear about the representation of the words.

So, the solution to all the above problems is pretrained word embeddings. Let us discuss different pretrained word embeddings in the coming section.

Also Read: Data Representation in Neural Networks- Tensor

What are the Different Pretrained Word Embeddings?

I would broadly divide the embeddings into Word-level and Character-level embeddings. ELMo and Flair embeddings are examples of Character-level embeddings. In this article, we are going to cover two popular word-level pretrained word embeddings:

- Gooogle’s Word2Vec

- Stanford’s GloVe

Let’s understand the workings of Word2Vec and GloVe.

Google’s Word2vec Pretrained Word Embedding

Word2Vec is one of the most popular pretrained word embeddings developed by Google. Word2Vec is trained on the Google News dataset (about 100 billion words). It has several use cases, such as Recommendation Engines, and Knowledge Discovery, and is also applied to different Text Classification problems.

Word2Vec’s architecture is really simple. It’s a feed-forward neural network with just one hidden layer, sometimes called a Shallow Neural Network architecture.

Depending on the way the embeddings are learned, Word2Vec is classified into two approaches:

- Continuous Bag-of-Words (CBOW)

- Skip-gram model

The continuous Bag-of-Words (CBOW) model learns the focus word given the neighbouring words, whereas the Skip-gram model learns the neighbouring words given the focus word. That’s why:

Continuous Bag Of Words and Skip-gram are inverses of each other

Example

For example, consider the sentence: “I have failed at times, but I never stopped trying”. Let’s say we want to learn the embedding of the word “failed”. So, here, the focus word is “failed”.

The first step is to define a context window. A context window refers to the number of words appearing on the left and right of a focus word. The words appearing in the context window are known as neighbouring words (or context). Let’s fix the context window to 2 and then input and output pairs for both approaches:

- Continuous Bag-of-Words: Input = [ I, have, at, times ], Output = failed

- Skip-gram: Input = failed, Output = [I, have, at, times ]

As you can see here, CBOW accepts multiple words as input and produces a single word as output, whereas Skip-gram accepts a single word as input and produces multiple words as output.

So, let us define the architecture according to the input and output. But keep in mind that each word is fed into a model as a one-hot vector:

Also Read: Building Language Models in NLP

Stanford’s GloVe Pretrained Word Embedding

The basic idea behind the GloVeword embedding is to derive the relationship between the words from Global Statistics

But how can statistics represent meaning? Let me explain.

One of the simplest ways is to look at the co-occurrence matrix. A co-occurrence matrix tells us how often a particular pair of words occur together. Each value in a co-occurrence matrix is a count of a pair of words occurring together.

For example, consider a corpus: “I play cricket, I love cricket and I love football”. The co-occurrence matrix for the corpus looks like this:

Now, we can easily compute the probabilities of a pair of words. Just to keep it simple, let’s focus on the word “cricket”:

p(cricket/play)=1

p(cricket/love)=0.5

Next, let’s compute the ratio of probabilities:

p(cricket/play) / p(cricket/love) = 2

As the ratio > 1, we can infer that the most relevant word to cricket is “play” as compared to “love”. Similarly, if the ratio is close to 1, then both words are relevant to cricket.

We can derive the relationship between the words using simple statistics. This the idea behind the GloVe pretrained word embedding.

GloVe learns to encode the information of the probability ratio in the form of word vectors. The most general form of the model is given by:

Also Read: Introduction to Softmax for Neural Network

Case Study: Learning Embeddings from Scratch vs. Pretrained Word Embeddings

Let’s take a case study to compare the performance of learning our embeddings from scratch versus pretrained word embeddings. We’ll also aim to understand whether using pretrained word embeddings increases the performance of the NLP model.

So, let’s work on a text classification problem – Sentiment Analysis on movie reviews. Download the movie reviews dataset from here.

Loading the Dataset into our Jupyter Notebook

#importing libraries

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

#reading csv files

train = pd.read_csv('Train.csv')

valid = pd.read_csv('Valid.csv')

#train_test split

x_tr, y_tr = train['text'].values, train['label'].values

x_val, y_val = valid['text'].values, valid['label'].valuesPreparing the Data

from keras.preprocessing.text import Tokenizer

from keras.preprocessing.sequence import pad_sequences

#Tokenize the sentences

tokenizer = Tokenizer()

#preparing vocabulary

tokenizer.fit_on_texts(list(x_tr))

#converting text into integer sequences

x_tr_seq = tokenizer.texts_to_sequences(x_tr)

x_val_seq = tokenizer.texts_to_sequences(x_val)

#padding to prepare sequences of same length

x_tr_seq = pad_sequences(x_tr_seq, maxlen=100)

x_val_seq = pad_sequences(x_val_seq, maxlen=100)Let’s take a glance at the number of unique words in the training data:

#Create a variable for the size of vocab

size_of_vocabulary=len(tokenizer.word_index) + 1 #+1 for padding

print(size_of_vocabulary)Output: 112204

We will build two different NLP models of the same architecture. The first model learns embeddings from scratch and the second uses pretrained word embeddings.

Defining the Architecture – Learning Embeddings from Scratch

#deep learning library

from keras.models import *

from keras.layers import *

from keras.callbacks import *

model=Sequential()

#embedding layer

model.add(Embedding(size_of_vocabulary,300,input_length=100,trainable=True))

#lstm layer

model.add(LSTM(128,return_sequences=True,dropout=0.2))

#Global Maxpooling

model.add(GlobalMaxPooling1D())

#Dense Layer

model.add(Dense(64,activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(1,activation='sigmoid'))

#Add loss function, metrics, optimizer

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='binary_crossentropy',metrics=["acc"])

#Adding callbacks

es = EarlyStopping(monitor='val_loss', mode='min', verbose=1,patience=3)

mc=ModelCheckpoint('best_model.h5', monitor='val_acc', mode='max', save_best_only=True,verbose=1)

#Print summary of model

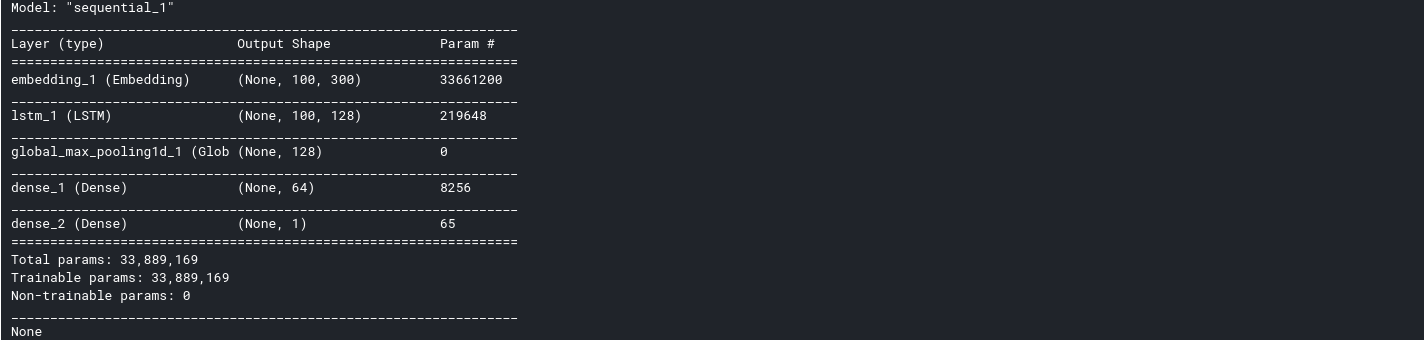

print(model.summary())Output:

The total number of trainable parameters in the model is 33,889,169, and the Embedding layer contributes 33,661,200 parameters. That’s huge!

Training the Model

import numpy as np

history = model.fit(np.array(x_tr_seq),np.array(y_tr),batch_size=128,epochs=10,validation_data=(np.array(x_val_seq),np.array(y_val)),verbose=1,callbacks=[es,mc])Evaluating the Model Performance

#loading best model

from keras.models import load_model

model = load_model('best_model.h5')

#evaluation

_,val_acc = model.evaluate(x_val_seq,y_val, batch_size=128)

print(val_acc)Output: 0.865

Now, it’s time to build version II using GloVe pretrained word embeddings. Let us load the GloVe embeddings into our environment:

# load the whole embedding into memory

embeddings_index = dict()

f = open('../input/glove6b/glove.6B.300d.txt')

for line in f:

values = line.split()

word = values[0]

coefs = np.asarray(values[1:], dtype='float32')

embeddings_index[word] = coefs

f.close()

print('Loaded %s word vectors.' % len(embeddings_index))Output: Loaded 400,000 word vectors.

Create an Embedding Matrix by Assigning the Vocabulary with the Pretrained Word Embeddings

# create a weight matrix for words in training docs

embedding_matrix = np.zeros((size_of_vocabulary, 300))

for word, i in tokenizer.word_index.items():

embedding_vector = embeddings_index.get(word)

if embedding_vector is not None:

embedding_matrix[i] = embedding_vectorDefining the Architecture – Pretrained Embeddings

model=Sequential()

#embedding layer

model.add(Embedding(size_of_vocabulary,300,weights=[embedding_matrix],input_length=100,trainable=False))

#lstm layer

model.add(LSTM(128,return_sequences=True,dropout=0.2))

#Global Maxpooling

model.add(GlobalMaxPooling1D())

#Dense Layer

model.add(Dense(64,activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(1,activation='sigmoid'))

#Add loss function, metrics, optimizer

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='binary_crossentropy',metrics=["acc"])

#Adding callbacks

es = EarlyStopping(monitor='val_loss', mode='min', verbose=1,patience=3)

mc=ModelCheckpoint('best_model.h5', monitor='val_acc', mode='max', save_best_only=True,verbose=1)

#Print summary of model

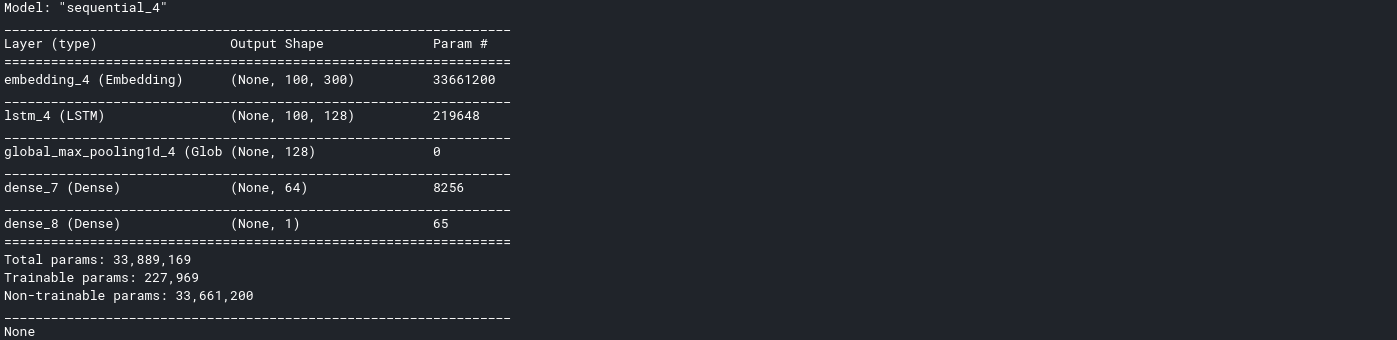

print(model.summary())Output:

As you can see here, the number of trainable parameters is just 227,969. That’s a huge drop compared to the embedding layer.

Training the Model

history = model.fit(np.array(x_tr_seq),np.array(y_tr),batch_size=128,epochs=10,validation_data=(np.array(x_val_seq),np.array(y_val)),verbose=1,callbacks=[es,mc])Evaluating the performance of the model:

#loading best model

from keras.models import load_model

model = load_model('best_model.h5')

#evaluation

_,val_acc = model.evaluate(x_val_seq,y_val, batch_size=128)

print(val_acc)Output: 88.49

Wow – that’s pretty awesome! The performance has increased using pretrained word embeddings compared to learning embeddings from scratch. You can run the codes, make some changes, and even try it with machine learning.

Conclusion

Pretrained word embeddings are the most powerful way of representing a text, as they tend to capture a word’s semantic and syntactic meaning. This brings us to the end of the article. I hope the English was understandable. In this article, we have learned the importance of pretrained word embeddings and discussed two popular pretrained word embeddings – Word2Vec-Embeddings and GloVe.

Also Read: Getting Started with RESTful APIs and Fast API

Frequently Asked Questions

A. Word embeddings are distributed representations of words in a continuous vector space/vector representation. They capture semantic relationships, enabling mathematical operations on word vectors to reflect semantic relationships between words.

A. The best pre-trained word embedding choice depends on the specific task and the nature of the data. Popular options include Word2Vec, GloVe, and FastText. The effectiveness can vary based on the domain and context of the application.

A. To train your own Word2Vec model, you need a sizable corpus of text data. You can use frameworks like Gensim or TensorFlow to implement the Word2Vec algorithm on your dataset and adjust hyperparameters for optimal performance.

A. While Word2Vec is powerful, it may struggle with out-of-vocabulary words and might not effectively capture rare or context-specific terms. Additionally, it doesn’t consider the order of words in a sentence, potentially missing some semantic nuances. Advances in models like BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) and GPT have addressed some of these limitations.

A. Cosine similarity effectively compares documents or text by focusing on the vectors’ direction, not the magnitude. It’s widely used in document similarity, clustering, and recommendation systems.

The Information will help a lot !

Awesome tutorial. Please, I have the following questions 1. Please, how can I split my dataset and load them as train/test split I can see that you used train/valid split. 2. How can I determine the performance of Recall, Precision, and F1-score after training of the model. 3. How can I tune my parameter for enhancing the performance of model

The article is really helpful. What about nlp pretrained models?